Investing comes up all the time in my conversations with clients. Everybody feels like they should be investing in some form or fashion, but they don’t always know where or when to start. This guide is a road map for people who are fairly new to investing for retirement and who want a solid foundation in best practices.

The average American retires at 64 (the official “full retirement age” per the government is 67). If you’ve made it to 64, you can statistically expect to live 18–20 more years, and you’ll need a nest egg to sustain those golden years beyond the pittance offered by Social Security (which only replaces, on average, 40% of your pre-retirement income). With numbers like that, you will likely need to become at least a millionaire just to retire in basic dignity someday.

The single biggest factor in having enough money to retire, for most people, is not where you put your money but whether you put enough money away. And unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, that can feel impossible.

And yet… I am continuously inspired by my clients who start out backed into a financial corner and somehow summon the strength to Spider-Man straight up the walls and into a better life. Many of us have more options than we realize, and it starts with recognizing what we’re capable of changing.

Even when we feel highly stressed out about our financial lives, many of us have an element of control — we just can’t see it through the fog. We can make choices to manage our money more intentionally. We can prioritize eliminating as many debt payments as possible and building liquid savings for emergencies. We can choose not to take loans from a 401(k) or withdraw contributions from a Roth IRA. We can choose to build a monthly spending plan that has enough squish to keep a strong savings rate, even when life happens.

And we can choose to make these things a priority now, because the earlier we start, the fewer dollars we need to come up with — thanks to the magic of compounding, we don’t have to actually come up with a million dollars! Steady, boring investing in low-cost, high-performing index funds will do most of the work for you. So let’s talk about what all of this looks like.

The tl;dr:

- You’re ready to invest for retirement after you’re out of high-interest debt and have at least 3 months of expenses in a high yield savings account.

- If you have low-interest non-mortgage debt, contribute 5% of your income every month to a tax-favored retirement account and work on eliminating debt.

- After you’re out of non-mortgage debt, contribute 15% of your income every month to a tax-favored retirement account.

- When I invest for retirement, I personally buy and hold index funds that follow the 10/10/1 rule: open for at least ten years, with returns of at least 10% over the life of the fund, and fees lower than 1% (although I really want them lower than 0.1% if possible); more on that below. If this is overwhelming, it is okay to pick a Target Date 20XX retirement fund (most plans have those), but you will usually see better returns if you pick the furthest out date available.

- No crypto, NFTs, single stocks, lottery tickets, 401(k) loans, or early withdrawals.

- Don’t change your strategy if the market goes up or down. Just keep swimming.

How do I know when I’m ready to invest for retirement?

If you have no high-interest debt and at least 3 months of expenses in a designated emergency fund HYSA (high yield savings account), you are ready to start. We talk about why you want to pay off high-interest debts first here.

If you have at least 3 months of expenses saved in your emergency fund, you should begin investing 5% of your household’s monthly take-home pay in retirement savings. While you do this, co-prioritize paying down low-interest debt with increasing your emergency savings to align with your risk factors. When your emergency fund matches your risk factors, you can dial up your total savings target.

Questions to assess your risk:

- Does your household rely on just one source of income?

- Is the majority of your income from self-employment?

- Is the majority of your income from a potentially volatile job? (Volatile, in this case, can mean an industry with high churn/seasonal fluctuations, or tied closely to the overall vibes of the economy; it can also mean a situation that feels unsustainable or precarious to you personally.)

- Are you prone to feeling financially anxious, even when things are going well?

- How many properties do you own?

- How many people depend on your income or time for their health and well-being? (This can include hands-on caregiving, or direct or indirect financial support.)

Give yourself 1 point for each “yes,” and add any actual numerical values for the last two questions. Divide this number by two. That’s the number of months you should add to the baseline starting number of 3 months. That’s your new target number for how many months of expenses you should have saved.

When your emergency savings are aligned with your new target number and you have paid off interest-bearing debts, you are well-insulated against risk. This means we can take on more investing risk — in this case, putting more money in retirement funds. This is risky because we can’t reach it without incurring taxes and penalties, and we definitely don’t want those if we can help it.

What should my retirement save rate be? What about my overall target?

The steady state, one-size-fits-most answer is that you should invest 15% of your household’s monthly take-home pay in retirement savings. A 15% starting target leaves you with enough extra to put toward other big goals, like saving for kids’ college or paying off your home, which will create more room for additional saving later. And 15% is a solid start to build on if you decide you want to do more sooner, or want to catch up to the traditional recommendations for how much you should have in retirement savings based on your current age:

- 30: 1 x your annual income

- 40: 3 x your annual income

- 50: 6 x your annual income

- 60: 8 x your annual income

- 67: 10 x your annual income

These recommendations are one-size-fits-most and are based on a “typical” retirement age of 67. If you are debt-free, have an emergency fund, and would like a bit more fidelity around your individual numbers, a simple retirement calculator like NerdWallet’s or Vanguard’s may be helpful—especially if you’re interested in retiring earlier than the standard age (I know I am!).

What kind of retirement accounts should I use? And when should I use them?

Depending on what you qualify for, here’s the recommended order for tax-favored accounts:

- Contribute as much as you need to take advantage of an employer matching contribution in an employer-sponsored plan (e.g., 401(k), 403(b), Thrift Savings Plan, SEP/Simple IRA).

In 2024, you can contribute up to $23,000 to an employer-sponsored plan if you are under 50 ($30,500 if you are over 50).- You don’t qualify for this step if… your employer doesn’t offer a match.

- You don’t qualify for this step if… your employer doesn’t offer a match.

- Contribute as much as you can to a Roth/Traditional IRA. If you qualify, a Roth is usually what I recommend for most people due to a combination of tax advantages and flexibility.

In 2024, the IRA contribution limit is $7,000 total per person per year (or your household’s total earned income, whichever is less). Individuals over 50 can contribute an additional $1000 (for a total of $8000). If you are a non-income-earning spouse, you can still contribute based on your spouse’s earned income as long as your tax status is married filing jointly.- You may not qualify for a Traditional IRA if… you (or you + your spouse) have no earned income that year. Most people can contribute to a Traditional IRA, but there are exceptions.

- You may not qualify for a Roth IRA if… you (or you + your spouse) have too little earned income (as with a Traditional IRA), but you can also be disallowed from contributing if your income is too high.

In 2024, the contribution limit starts at a modified AGI of $146,000 (single filer) and $230,000 (married filing jointly).

Note: Modified AGI is a bit confusing and requires diving into your tax return, but it’s usually close to your AGI for most people. If your regular AGI from your tax return isn’t close to those thresholds, then you are likely okay.

If your salary/AGI are close to or over the limit, you can use this IRS worksheet or consult with a tax professional to figure out whether you’re over the line.

If you are a high earner who winds up disqualified, you may use a tax strategy called a Backdoor Roth IRA (here’s a short how-to if you are lucky enough to have this problem!).

- Contribute the rest of your 15% in your employer-sponsored or other tax-favored plan. If you work for a small business, you may not currently have an employer-sponsored plan; it may be worth checking with your employer to see if they are willing to set up any type of retirement plan (there can be tax benefits and credits for small-business employers who do this!). If you are self-employed or a gig worker, there are advantages to setting up a tax-deferred retirement saving plan like a solo 401(k), a SEP IRA, or SIMPLE IRA for yourself. Again, this is best done in consultation with a tax pro.

What all this looks like in big-round-numbers practice:

- You earn $100,000 per year, so you know you want to contribute 15%, or $15,000 total, to your retirement accounts.

- Your employer has a 4% match, so you would want to contribute $4,000 for sure (get that match)! After that, you still have $11,000 you need to allocate.

- You have enough left to contribute all $7,000 to a Roth IRA, so do that.

- With the remaining $4,000, you would dial up your contributions to your employer so your total annual contribution would be $8,000.

If you go through the steps with your own income and run out of money before you reach the end of the steps, that’s okay — the important thing here is maxing out any match money and hitting 15% total, whether or not you manage to max out an IRA.

If you are someone who likes to take your tax return or bonus and dump it all in a Roth IRA, that’s okay too – just factor that into your overall calculation for the year.

And if you still have some of your 15% left after you’ve done all you can in tax-favored accounts, you can then move on to non-retirement brokerage accounts, real estate, and other investment types. But start with the tax-favored stuff because you want to catch those tax breaks where you can!

What are “low risk” versus “high risk” investments? Should I be “aggressive” or “conservative”?

If you tell an investment algorithm or professional you are “risk averse,” they will almost definitely recommend a mix of less-volatile (“low risk”) but also slower-growing (“low reward”) investments. But unless you are within a few years of your desired retirement age, we are talking about money that will sit in the dark and grow quietly for a LONG time. If you are protected against risk in other areas of your life, you have room for more risk here.

I personally take a long view, and opt for low-cost index funds with strong returns over a long track record, even though that’s considered “high risk.” I want the long-term high rewards of compound interest from so-called “aggressive” investing. The risk from long-term investing in well-diversified index funds doesn’t scare me because I’m protected against short-term risks. I have a fully funded emergency fund in a high-yield savings account to cover short-term needs, my household has an adequate mix of insurance coverage, I don’t put anything in investments that I might need within five years, and I don’t plan to touch our retirement accounts until I’m actually retirement age. So my own strategy is to be aggressive, but from a risk-insulated position.

Do I need to hire an investment professional?

I have not used a financial planner yet, but I do have several excellent and trustworthy ones in my network whom I would call if I found myself in a position where I was concerned about tripping a tax wire or meeting a time sensitive goal. There are a few tipping points where I think it becomes worth it for many people. (If you’re at one of those points, I’ll be happy to refer you to someone!)

Most advisors get paid their fee whether they make money or lose money for you, so you must proceed with caution and ensure you’re getting real value for your money! Good investing is boring and straightforward, and it is not complicated to learn how to narrow down the field to good options. If you are many years out from retirement and have a straightforward financial life, and all you can afford to do right now is invest in your workplace account and in a basic Roth/Traditional IRA, I strongly believe it’s worth your time to learn how to do self-directed investing in low-cost index funds.

However, a skilled investment professional brings unique expertise in specific areas, and I think the most valuable of those skills involve developing investment and withdrawal strategies if you plan to start taking money out within 5 years, and navigating potential tax issues (which can come into play for both investing and withdrawing). Here are some situations where it makes sense to have at least a consultation with a financial planner:

- If you are an extremely emotional investor who is prone to toxic “buy high, sell low” behaviors (or if you’re married to someone who is), it is probably worth the cost to hire a trustworthy professional that can protect your household from your worst instincts until you get those unhealthy knee-jerk reactions sorted out.

- If you have maxed out your employment and Roth/Traditional contributions and haven’t come close to touching 15%, an investment advisor can help you find appropriate ways to diversify your portfolio without triggering tax issues.

- If you are within 5-10 years of retirement, even if you think you have enough saved, it is probably worth it to ensure you are set up with a good “mix” that suits your timing and tax needs.

- If you have any other unusually complicated situation (tax, employment, family, property, or otherwise), then it’s wise to call in a pro.

- If you simply have no interest or aptitude for learning this stuff at a level that you feel comfortable with, you can outsource this. However, you will still have to do enough work (or call in enough support from a financially savvy friend) to avoid anyone trying to take advantage of your lack of interest.

For a consultation, I recommend looking for a Certified Financial Planner (CFP) who is willing to explain stuff to you like you’re six, not someone who is going to coax you into stuff that isn’t in your best interest by using fancy financial jargon or scare tactics. It should be someone who is bound to act as a fiduciary, which means they must act in your best interest. Fee-only advisors are only compensated by money you pay them — either directly as a flat or hourly rate, or as a percentage of assets under management (AUM) — and they are typically fiduciaries. Fee-based advisors can receive commissions from products they sell to you, in addition to fees they earn from you; if they are not acting as fiduciaries, this may create a conflict of interest. You should absolutely ask an advisor about this in your consultation (notes on these differences here).

If you only have workplace + IRA accounts to contend with, or you are a DIYer with time-sensitive goals or needs (including early retirement!), you are probably better off opting for a “project-based” planner who works at an hourly rate to create a plan for you.

Also, and this is important: some financial planners are secretly whole-life insurance salespeople, and almost no one needs whole life insurance. It is almost always a waste of money. Except in unusually high-net-worth cases where it can serve as a tax shelter, it’s an outlandishly expensive product for what you actually get in return, and your money is virtually always better invested elsewhere. Whole life will never make you rich, and anyone who says differently is selling something. (Or was sold to, and now has a bad case of cognitive dissonance.) As such, I do not recommend working with financial planners at a company that is primarily based on insurance sales. When networking, I personally always make sure to ask financial planners about what insurance products they recommend to their customers. The right answer sounds something like “most clients only need term insurance, and whole life is something we only recommend as a tax shelter for very high net worth cases.” Anything else should make you head for the door.

How should I pick investments if I’m doing it myself?

I am not an investment professional and am not giving investment advice, but I am teaching you how I personally evaluate investment options. I choose index and mutual funds with long track records of strong performance and very low fees (also called “expense ratios” or “loads”). Index funds are portfolios of many stocks based on a specified chunk of the financial market—and because of this, the funds are somewhat internally diversified. I do not prefer actively managed funds because most reports show that actively managed funds tend to underperform index funds, and passively managed index funds also tend to have much lower fees.

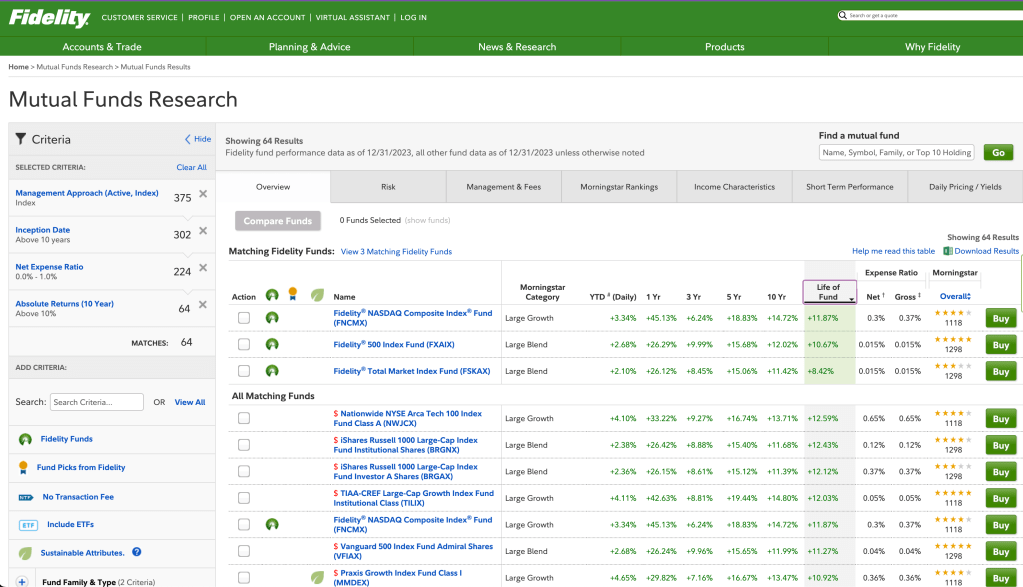

When I am shopping for funds, I like investing in low-fee index funds with long track records of high returns. I call it the 10/10/1 rule: I look for index funds that have been open for at least 10 years, with 10%+ returns over the life of the fund, and fees (a.k.a. expense ratios or “loads”) of less than 1% (preferably lower than .1%).

Here is what that looked like in practice when I looked at index funds recently (Jan 2024) with Fidelity’s research tool, which is available to the public. (We currently have our accounts there and it’s been a good experience; not sponsored, just sharing what we use!) You can see the filters on the left have yielded 64 funds, and most of those are currently big swaths of the market and tech stocks (it is, after all, a snapshot from January 2024).

However, if you don’t want to fuss with any of this yet, a perfectly fine option is to pick just one Target Retirement Date fund with good returns and the furthest-out retirement date you can get (past the year you actually want to retire!). I know it sounds weird, but we recommend picking a later date because the mix of stocks and bonds in those funds begins “aggressive” and automatically shifts to a more “conservative” (usually bond-heavy) mix as you approach the stated retirement date. We want high-performing investments for as long as possible to capture the high rewards of compound interest. Target date funds are typically internally well-diversified and have low fees, and many employer plans have them as an option. They’re often a good choice, but you should still look at the actual numbers to see how they stack up to the other available offerings.

In the end, it’s much better to start investing in a smart, simple way than to get overwhelmed by your options and not start at all.

Are there any investment strategies I should avoid like the plague?

- I do not buy cryptocurrency or NFTs, (aka non-fungible tokens, which I am pretty sure aren’t even a thing anymore but I’m leaving it in here in case the hysteria comes back). Crypto soared, then crashed, and now the buzz around spot Bitcoin ETFs makes it sound like you need to get smart and get in there, even though most of us have knowledge about three articles deep. These “investments” are too risky for us to bother touching. Also, it’s an environmental disaster. Just… no.

- I don’t try to time the market. We are buy-and-hold investors who invest steadily in our chosen mature low-fee index and mutual funds every month. (Though, if we have extra money lying around in a given month, we might go bigger if the market is down—as Mr. Fortuna likes to say, “stocks are on sale!”) We don’t get emotionally involved in our investment account balance. We don’t plan to withdraw our retirement funds until retirement.

- I don’t save money in non-retirement investments if I think I might need it within five years. When you’re talking about the whole market—which is how we’re investing, since we’re all about those index funds—you have to remember: down days/weeks/months/years happen and down decades almost never do. From 1927-2018, 94% of 10-year periods have been positive for the S&P 500. Try to stop worrying and love the market, but don’t put anything in there that you might need sooner than five years!

- I don’t mess around with single stocks. Once, I was chatting with a friend who thought their buddy should hang on to a single stock instead of liquidating it to pay down debt. In this case, the single stock was Berkshire Hathaway.

Me: I don’t like single stocks. I say he kills it and gets rid of the debt.

Friend: Well, Berkshire Hathaway isn’t really a single stock… but maybe he should sell; I am kind of worried that Warren Buffett might kick the bucket soon.

Me: … and that’s why I don’t like single stocks. “One guy dies and the company might flail” is not a part of my long-term investment strategy.

If you were betting on football, would you bet bit money on the health and success of a single player? Does it feel safe to bet on just one team? Or instead, do you want to bet on the continued success of the whole NFL? If you think it’s super fun to invest in single companies, treat it with the same attitude that you would treat gambling in Vegas—as a way to have fun but not as a serious retirement plan. If you get super lucky? Awesome! If not, you didn’t lose anything that would stress you out. - Finally, I don’t do early withdrawals or loans against retirement accounts. That’s not really investing—in fact, it’s the opposite—and we don’t recommend it except as a last resort (e.g., to avoid bankruptcy/foreclosure).

If you want help tailoring these recommendations to your individual situation, I’d love to see you on my calendar.