What is a HYSA and why is it awesome?

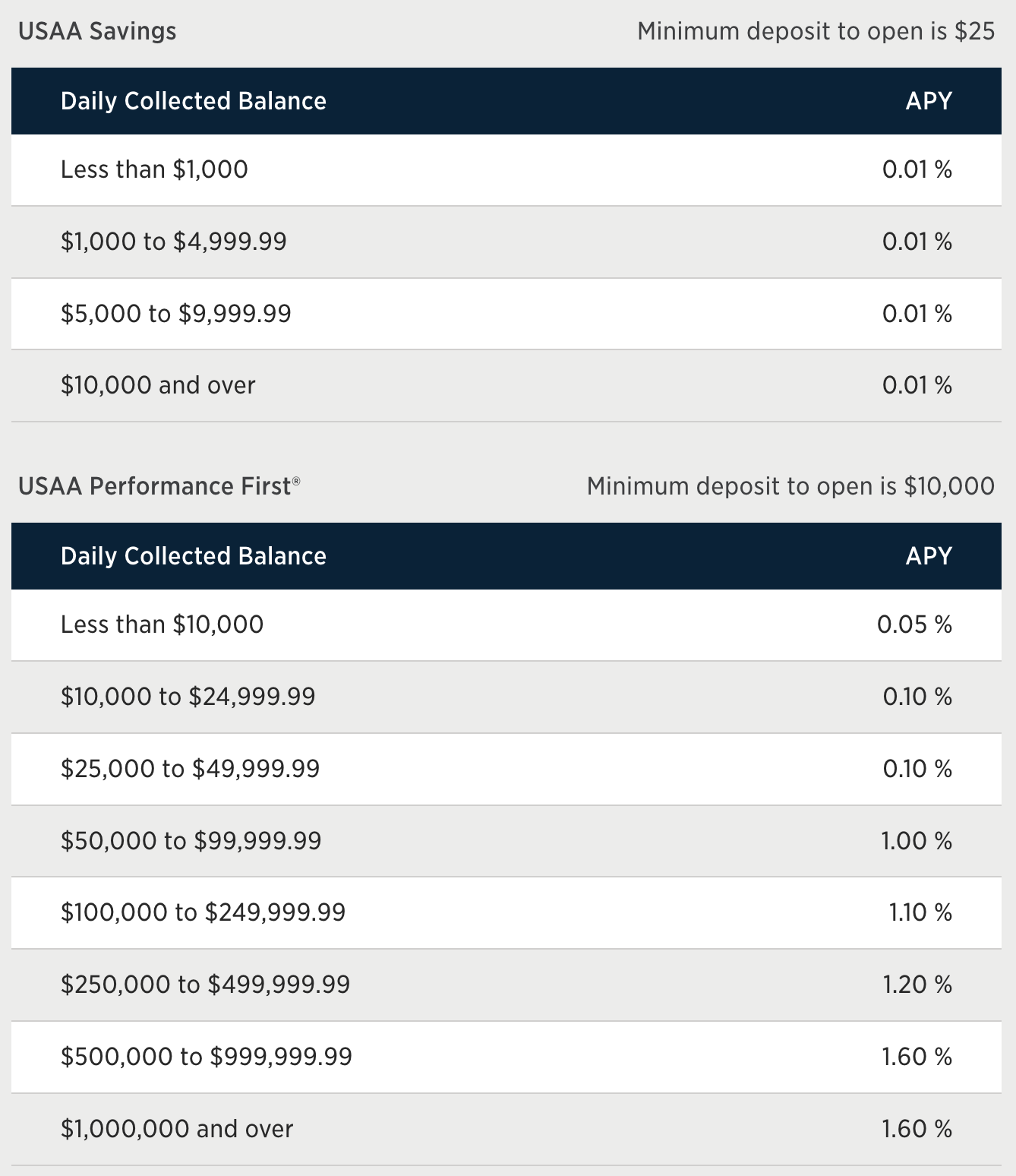

A High Yield Savings Account is a savings account with a MUCH higher “Annual Performance Yield” (APY), a.k.a. interest rate, than a traditional savings account. We currently do most of our personal banking with USAA, and here are their current savings account rates:

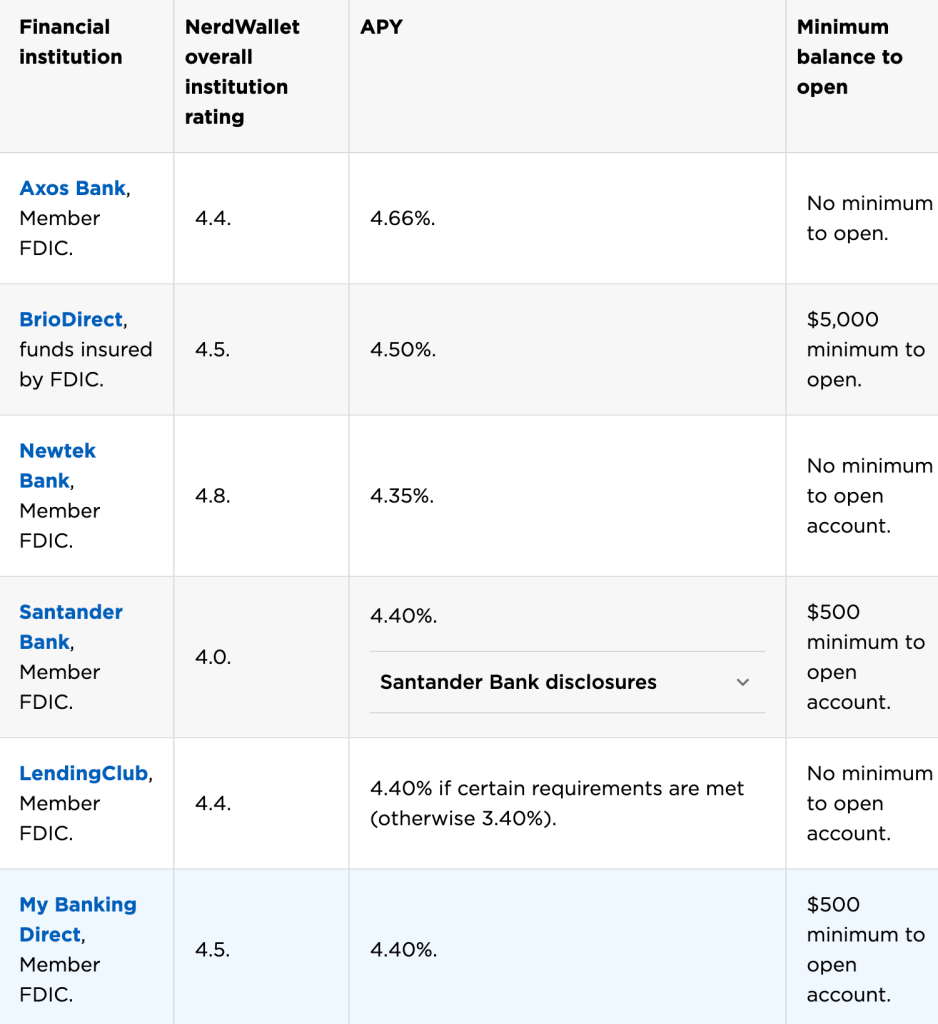

Meanwhile, this is what the interest rate spread looks like in a section of the current roundup from Nerdwallet:

0.1% vs. 4.5%? We don’t even need a calculator for this one!

So you know that these accounts are offering super high rates of return. But you are a savvy and thoughtful individual, so I imagine you’re wondering, “what’s the catch?”

The catch, if you want to call it that, is somewhat limited access, compared to a traditional brick-and-mortar bank. Most HYSA banks are either fully-online, or the digital-only subsidiary of a traditional bank, so everything you do will be online. For an HYSA specifically, you probably won’t have a debit card or a checkbook (although some online banks offer one or both!), so you usually need to transfer money back to your primary checking account before you can spend it. And some of the money that your bank is saving on all this overhead, they’re passing on to you in the form of high interest returns.

But before you balk at this: I contend that limited access for your emergency/peace of mind/safety fund is a feature of these accounts, and not a bug.

Most of us need a little friction before we dip into savings. Our brains suffer from a bias that loves to prioritize small immediate rewards over large long-term rewards (“hyperbolic discounting” if you’re nasty). If you haven’t done the work to strengthen your money habit muscles, you may be tempted to use emergency/purpose-directed savings to cover an impulsive moment. Hiding this money away where it’s a little bit harder to get to is a great strategy for protecting your long-term well-being!

How to choose

Now, it’s time to pick one. For the latest recommendations on High Yield Savings Accounts I usually look here or here. Rates and bonuses change all the time, so kick the tires a bit to see what looks good.

Whatever you pick, we want to make sure it has no minimum balance requirements or fees, and a high interest rate. Those are the core requirements.

Next, ask yourself what matters to you: does it have a debit card? is there an app? can you write checks? how hard is it to move money into or out of it? None of these are general dealbreakers, but instead are based on your personal preferences.

Why HYSA and not MMA or CD?

Two questions I have been asked before:

- why a HYSA and not a money market account? The short answer: money market accounts (MMAs) that have no fees, no minimum balances, and equivalent interest rates are A-OK! But many of them do have minimums, and getting penalized because you had to withdraw savings to cover an emergency feels like salt in the wound.

Also… many money market accounts are with investment companies. If there’s any chance you’d be tempted to move your savings from a money market fund into something more aggressive, I’d hesitate, since we don’t want to invest our emergency fund. (More on that in a sec.) - What about CDs? CDs are a no-go in my book as your primary emergency fund because you can’t withdraw the money on your timeline without incurring penalties or fees… yet the rates are not usually significantly better than a HYSA! If the interest rate climate starts to change, or if you’re someone who really wants a strong disincentive to dip into a specific chunk of your savings, I can see why you’d opt for a CD… but it’s still not my top recommendation.

Since, no matter what, we’re picking an account that has no fees and no minimum balances, you can open more than one at the same financial institution, which we’re going to do. One is for safety, and one is for treats.

Safety first: what to do with account 1

Whether you call it an emergency fund, a safety fund, a peace-of-mind fund, a rainy day fund, or something else entirely (and if you have a strong opinion about this, please tell me, I want to know!)… you need to have one. Here are the guidelines for how big it should be, when you should use it, and why we don’t invest it more aggressively.

How much?

If you’re starting from scratch and you have high-interest debt or feel like you’re barely living paycheck-to-paycheck, I recommend starting with a goal of $1000, or two weeks of pay — whichever is less. We will then switch focus to hammering your high-risk debt into smithereens.

If you have no debt, or a manageable amount of low-interest debt, I recommend aiming to put 3-6 months of expenses in this account, although you can go as high as 12 if your life carries high risk. Questions to assess your risk:

- Does your household rely on just one source of income?

- Is the majority of your income from self-employment?

- Is the majority of your income from a potentially volatile job? (Volatile, in this case, can mean an industry with high churn/seasonal fluctuations, or tied closely to the overall vibes of the economy; it can also mean a situation that feels unsustainable or precarious to you personally.)

- Are you prone to feeling financially anxious, even when things are going well?

- How many properties do you own?

- How many people depend on your income or time for their health and well-being? (This can include hands-on caregiving, or direct or indirect financial support.)

Give yourself 1 point for each “yes,” and add any actual numerical values for the last two questions. Divide this number by two. That’s the number of months you should add to the baseline starting number of 3 months.

- A single active-duty military member who rents a house and feels no financial anxiety? 3 months is probably plenty (yes, it’s just one income stream, but it’s a really safe income stream).

- A dual-income homeowner household with two kids, where one partner is self-employed and one partner is prone to financial anxiety? Five to six months might feel more comfortable.

- The household of a divorced advertising entrepreneur who is responsible for three teenagers and an aging parent, who also has three rental properties in addition to owning their home? I’d seriously consider at least eight months of expenses.

Remember, three to six months is the financial community consensus for how big an emergency fund should be, but that number is based on expenses, not income, so it is hopefully more than your net pay. (If it’s not, we should definitely talk.) If you’re an aggressive saver, or you have a high level of discretionary spending that you know you could cut if you had a major problem, you can lower your expense number accordingly.

When should you use it?

This litmus test is comprised of the three questions that we (in my household) ask ourselves before we use money that’s in our emergency fund:

- If I don’t spend this money to solve this problem, will it affect my household’s health, safety, or earning ability?

- Do I have to solve this problem immediately, or can I wait and save over time to address it?

- Can I find any of the money to solve this problem in my current month’s cash flow by moving things around, or forgoing something discretionary?

This trio of questions reminds us that the money is there to solve a problem. “Wanting to go on a vacation” or “voluntarily upsizing a car” is not a problem — it’s a goal to plan and save for separately, in its own account. By putting tight parameters on when emergency money is fair game, you can make more aggressive moves elsewhere in your financial life, and you can also ensure that an emergency doesn’t cannibalize your goal savings for something important and life-giving (like that vacation!).

And if you do need to dip into it at any point, you’ll just rewind back to the same process you used to fund it in the first place. (I have a li’l roundup of tips to grow your savings here.) This may mean that you need to temporarily pause other retirement or goal savings and trim your discretionary spending, but you will have already done it once, so I’m confident you’ll be able to do it again.

Why should I do it this way, instead of just investing all that money? Aren’t I leaving money on the table?

You might be someone who lives within your means and has low-to-no debt. Perhaps thus far, you’ve been able to tweak your spending to save quickly for any time-sensitive need that might have affected your health/safety/earning ability (or any such need has been small, or maybe hasn’t come up at all). If that’s the case, congratulations on both your good choices and your good luck! Because you’ve never needed emergency savings, you may feel like it’s silly to keep this much money on hand when you could grow it aggressively in low-cost index funds… but hear me out.

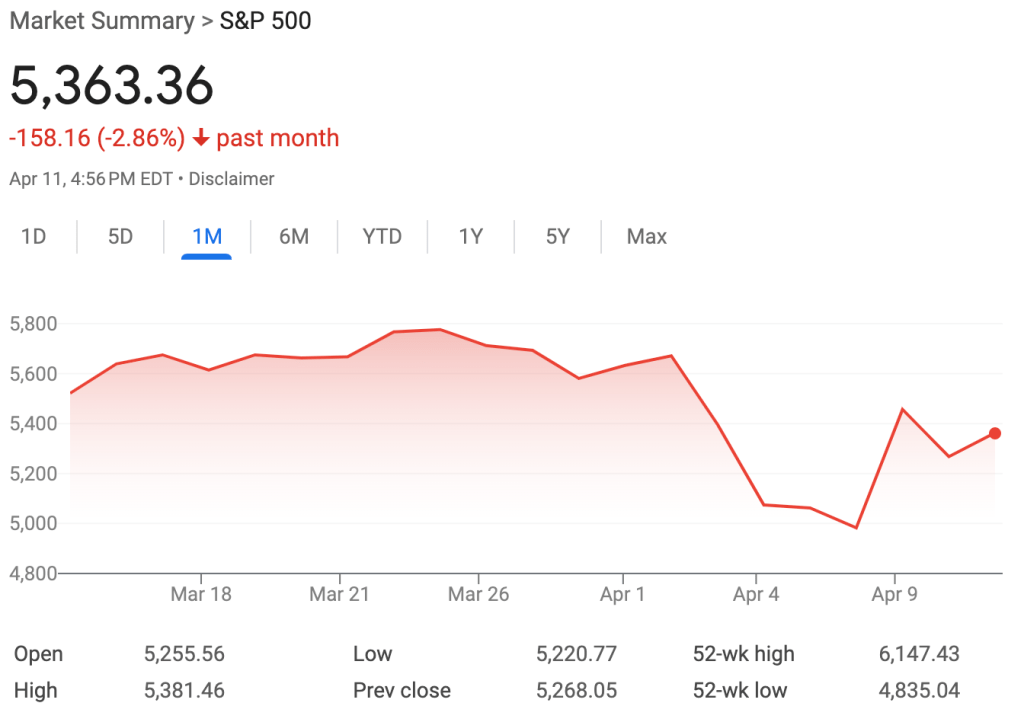

The point of your emergency fund is to insulate you against risk, not to make you money. It’s more like insurance than an investment, and it protects you so you can go out there and be more aggressive elsewhere. Your emergency fund is there for you to use when you absolutely no-kidding need it, so you won’t have any stress about paying a penalty or selling at a low point. Just as an example: if you needed money in a time-sensitive way on April 8, 2025 and all you had available to cover it was investments, I suspect you would have been fairly upset.

Your emergency fund is for unsexy, necessary, time-sensitive stuff that keeps the roof over your head and wheels on your car. Yes, there’s a small opportunity cost by just earning 4% on a large chunk of money… but so many of the people I work with would be much happier today if they’d had 3 months of cold cash set aside for an emergency, instead of “temporarily” floating a credit card or two that spiraled out of control. These people are all really smart and have made lots of other good financial decisions — including investing aggressively for retirement! — but simply did not have available cash-on-hand to manage a streak of bad luck.

The counterweight here is that we do cap our emergency fund at a finite and risk-based amount, because you’re not wrong: it IS silly to keep all your money in savings when you could be investing it in low-cost index funds and reaping big returns. I’m willing to pay a small opportunity cost to insulate me against risk, but I don’t want to pay it on all my money! This approach properly treats your emergency fund as a type of insurance that protects you from taking on debt, liquidating investments, or withdrawing from retirement accounts (and paying attendant penalties and fees)… so you can enthusiastically invest elsewhere without worrying that a market downturn will wreck your finances.

I sincerely love investments when we’re talking about money that you don’t need in any kind of time-sensitive way. I follow the financial community consensus that the markets are for money you don’t need for 5+ years, so you have time to run with the bulls and ride out the bears. My emergency fund’s slower rate of growth is a price I happily pay to be able to quickly use cash, so if something dire happens I won’t need to sell investments at a low point, which come with an opportunity cost of their own.

Treats and savin’, savin’ and treats

We’re going to be quick about this because I don’t think you need me to teach you how to dream (although tell me if you do, ‘cause I will be happy to help).

Once you have your emergency fund fully funded, it’s done. Unless you have a change in circumstances that recalibrates your risk-o-meter, your emergency fund number is The Number. That’s it. You don’t have to add to it, you don’t need to save more “just in case,” you don’t need to worry about it. You’re done. Woohoo!!

At this point, with a fully funded emergency fund, I would strongly recommend ensuring that you’re saving at least 15% of your household’s monthly take-home pay for retirement, so future-you is as financially comfortable as present-you is now. If you have kids and want to help them with their education, it’s also a good time to start planning for that.

But both of those are steady-state drumbeat operations that run in the background, and it’s time to think big.

So… what do you want?

What can you reasonably anticipate needing, desiring, or upgrading in the next one-to-five years? We saving for a house down payment? Buying a nice new car? Planning for a luxe yoga retreat? Taking a sabbatical to learn Italian cooking in Italy? Your second HYSA is the perfect place to save for that. Basically, anything that’s not an emergency but requires more than a few months to accumulate should go here. Those few months will add a little bit of interest that helps you reach your goal faster, rewarding you for your patience and incentivizing your progress.

What about even longer-term goals?

It’s okay to use an HYSA for far-future stuff too, but cash for longer-term savings goals can grow more productively in the markets. With a >5 year time horizon, you have the time to reap benefits and ride out the downturns, particularly if your goal isn’t tied to needing all the cash at once on one specific date.

If your dreams are more “going HAM on investing so I can retire early and be my own sugar daddy,” first of all, I love that energy and I want to help you do this, and read Work Optional if you haven’t already. Whether your dream is to actually retire early, or you simply want to hit a major goal with a longer time horizon, I’d recommend doing some serious planning and research on how to structure it. This may include working with a project-based CFP to run a risk-assessment that makes sure your plan accounts fully for risks and tax hazards (let me know if you need a recommendation, I have several!).